Wednesday, January 14, 2026

Saturday, January 3, 2026

Tuesday, December 30, 2025

Saturday, November 1, 2025

Thursday, July 24, 2025

Saturday, June 21, 2025

Cherry Bounce Update

In 2013 I transcribed a recipe from La Tasse Cafe radio program about a curious drink called cherry bounce:

"Cherry Bounce is a thick sweet strong liqueur that people in south Louisiana make around the holidays. You shake the wild cherry trees (merisiers) so that the berries, called merises or choke cherries, fall onto a sheet."Wednesday, June 18, 2025

Recette pour le jour-même Cherry Bounce

Recette pour le jour-même Cherry Bounce

C’est le mois de mai et j’après trouver encore les merisiers pour faire mon cherry bounce. Il y un merisier sur une île dans le Bois de Chicot chez ma famille, c’est là àyoù j'ai été le jour. C'était le jour même, la première fois, un dimanche matin. L’après midi, j’étais dans le merisier sur l'ile et ces merises noirs que j'ai tant espéré pour tombait autour de moi. Pour asteur c’est le mois de mai et je peux voir que toi aussi t’as paru dans ce temps de mûrage.

Quand j’ai vu ces merises après pendre comme des régimes des raisins, plus que jamais, j’ai pensé à toi. Un beau cou-lève noir et vert glissait à côté de mon pied. Equand j’ai secoué l’arbre, équand j’ai pris le pôle pour battre les branches et les merises tombaient sur le drap. J’ai pensé de comment c’est bon pour un arbre d'être touché comme ça dans l’avant printemps, ça le fait produire plus des fruits. J’ai lavé ces merises dans le soleil avec rien que mes mains, ôté les tiges, équand j’ai mis mes merises en bas de l’eau fraîche encore et encore, j’ai pensé à toi. Equand j’ai séché chaque petit fruit, je les ai admirés. Comment ça brillait. J’ai pris chaque merise pour drop un à la fois dans le cou de bouteille, doucement, chacun représentait la patience et l'espérance qu’il faut pour faire ça tourner en sirop, pour faire un fruit aigre, doux. Je les ai couvert de sucre, remplis la bouteille de whisky. Je faisais tout ça avec mon amour des choses bien faites, bien mûres, des fruits noirs et rares dans les bois, entourés de l’eau. Chaque merise que j'ai mis, j'ai parlé de mon coeur, en remerciement pour ces fruits, ce medicine, ce connaissance, et en espérance que comme ces merises chaque année, que toi tu vas revenir encore et encore, et que tu vas être là pour partager le cherry bounce avec moi dans avenir, dans le temps des fêtes.

Monday, April 28, 2025

Vinéraire

In 2012 there was a persistent maple syrup smell that hung in the back of my pasture. Having had enough familiarity with the other medicines, remedies and prairie plants, I began to scrutinize the individual plants in the back corner, and it was easy to find the one because I knew the others. I often identify familiar plants for my own needs through crushing the leaves and smelling them. If you know a plant well and work with it, this method is reliable. This plant's smell was unique. After some identification (it was pseudoghaphalium obtusifolium, fragrant rabbit tobacco, life everlasting, vinéraire), I let the season pass. Each time I returned to the back pasture it was no longer in that spot.

I still looked occasionally and asked around about a plant with this maple smell, but I lost it. Eventually I arrived at a time when I had a mental critical mass of native plant experience through my transcriptions of my hometown's Creole folklore. Sometimes I would set an intention to find a plant like herbe à vers, or wormseed (to make the traditional de-worming praline) or herbe à malo, aka lizard's tail (to make the teething necklace) and go out and find them somewhere in the prairie or swamp. It was in this way that in the summer of 2023 I finally found three vinéraire plants again in the side pasture. I cleared the other plants from around her and allowed her to grow. I also began to carry a spring with me everywhere I went. It was a sad time and I sat with the plant often and began to use it medicinally and spiritually. I never left home without it and it was with me through some tough times and gave me comfort for its smell, softness and as I began to learn, local rarity.

In this time I had a meeting with some folklorists and horticulturalists who I shared my curiosity with. They knew what it was but were incredulous that I had found it with my nose in the pasture. They eventually produced letters and contacts of local healers and Indigenous women who were 40 years in search of the plant, because it was now hard to find down the bayou.

I learned that it's a mid succession species that comes when the prairie is healing and becoming more diverse, but that it usually grows in undisturbed prairies, which my field is not; it was farmed for decades. Still remnants might remain at the edges, and memory remains in the land always.

Over the last three years I have observed this plant at all stages and seasons, through snow and drought. It likes liminal edge and dry soil. This could be one of the reasons that it appeared here, among others. It has spread voluntarily across my back pasture from three to around 700 (this year, so far) individual plants. It has spread on its own, under conditions that I monitor, and does not yet she grow where I plant her.

I make sprays, balms and burn it regularly as one would burn sage. I have documented its native uses, etymologies in Creole, French and Choctaw, as well as its extensive spiritual connections. I have shared in ongoing art exhibits such as Botanica at the Louisiana State Museum at the Cabildo in New Orleans as well as the Prairie Stories exhibit Acadiana Center for the Arts in Lafayette, Louisiana. I have given lectures about it for several college classes in Louisiana and out of state, as well as at Basin Arts, Academy of the Sacred Heart, Nunu's, Atelier de Nature and at a workshop at Balfa Week.

I have had the most satisfying honor of providing the plant and seed to the women and men who were in search of it, as well as herbalists, traiteurs, healers, and a few of the members of the Indigenous tribes in order to return its medicine to the people of south Louisiana.

Wednesday, April 16, 2025

Tuesday, April 15, 2025

Tree Medicine

Tree medicine.

There was a white pine that volunteered in the western yard. It obstructed my view of the open prairie to the southwest, so he chopped the top for my photography. That cleared the view for a few years but that tree continued to grow. Except now, at the injury, it weeps sap. I’m not sure if it’s a memory of the damage that was done to clear the path, or if sickness or parasite still lives in the tree. No matter, it has become a medicine tree. On walks around the property I stop there and check the ground for chunks. I follow their fall patterns and gather them. At first I kept this sap and chunks of resin in my journals, not knowing what to do with it except smell it and let it perfume my journal. Sometimes I put the clearest sap on small cuts around my cuticle.

One wet Louisiana winter day I went out to build a little fire in the wax myrtle bower but everything was damp. I pulled out the pages of my journal with the resin on them and they worked fine, similarly to the bois gras the men collected and used for fire starter. It kept my little fire going and kept me warm that day and others. It became a habit of mine to be able to spot injuries on resin trees and check them no matter where I was. I kept the pieces of resin in a tin can painted with blue and gold stars on the porch. But one day an indigenous friend gave me a balm made of bear grease and five kinds of fir resins from the north, saying that it would heal any wound and not even leave a scar. I knew then what to do with my resin collection.

I melted the chunks down with sweet almond oil and when they were warm and incorporated, filtered it and mixed it with melted bay wax from the bower to make a balm that my boys called “tree medicine”. They refused Neosporin but would accept the tree medicine on their wounds, only after I showed them the tree itself.

Daily I work atop the Grand Coteau at a school over 200 years old, full of old oak and pine allies. Some of the pines seem to be nearly as old as the school and bare many scars and knots that give sap. I immediately began to survey each tree at recess and the girls would ask, "Madame, what are you doing?" Last year, one of the largest pines was struck by lightning and it created a rip in the bark that began to weep sap. Daily the girls and I go out and check this tree, because it gives the clearest sap that looks like tears. I have taught the girls that only the wounded trees will give the medicine, and in their healing, we can also share in it a little. I explained that the sap is like the tree’s blood and the resin is the scab. They apply it, like me, to their cuts, and know that hand sanitizer will clean it and cut the stickiness. I make a spray with the resin also that I

use daily as a hand cleaner. Sometimes I come to my classroom and there are curious pine sticks on my desk that upon further inspection are tipped with sap. They'll make a resin platter out of a piece of bark, or dig into a knot with sticks often creating more injury and then more sap. One time I found a half pound chunk of resin, who knows how old, on my desk and thought it was a chunk of tasso. This morning as I was out there in my petticoats and cape gathering fresh pine sap tears with a ruler, and curious as it is, none of the girls even asked me what I was doing.

Wednesday, March 12, 2025

I ain't worried bout Josephine

Lafayette Louisiana's group Da Entourage (The Entourage, also in Creole: the wall) came out with the regional hit The Bunnyhop in the 1990s. Da Entourage was formed by cousins Toemas (Griffin) and Alley Cat (Zeno), and their childhood friend Bunny B. (Brown).

When I hear this song I can't help but notice the hyper-local French Creole feel of the use of the name Josephine in the lyrics:

I'm so glad I got my own/I ain't worried bout Josephine

My life's a natural high/C'mon and bunny hop with me.

Martiniquaise Josephine Bonaparte, married to Emperor Napoleon, is perhaps the most famous owner of the name in the French Creole world, but as a Louisiana Cajun/Creole musician and writer, I can't help but feel the idea of this woman Josephine has trickled down from the echos of our popular music's past and into the Lafayette hip-hop scene. Something about the lyric "Josephine c'est pas ma femme" is giving the same energy as "I ain't worried 'bout Josephine."

Here I'll list as many songs as I can that mention Josephine in Cajun or Creole music.

La Valse de Josephine by Leo Soileau and Sadie Courville

Malheureuse, mais 'garde la bas la 'tite poussière, chère, de ti neg qui s'en vient, ti-galop chez Josephine.

Unhappy woman, look over there the little dust, dear, of your man who's coming at a cantor from Josephine's house.

My Josephine Hackberry Ramblers

Josephine oh my Josephine, t'es une jolie 'tite fille/Josephine, ma Josephine tu connais tu me fais m'ennuyer/ Tu m'as dit qu tu m'aimais/ Mais moi j'connais ça c'est pas vrai. Ma Josephine.

Josephine, oh my Josephine, you are a pretty little girl/ Josephine my Josephine you know you make me lonely/ You told me that you loved me/ But I know that's not true/ My Josephine

Josephine c'est pas ma femme by Clifton Chenier (Queen Ida/Fatz Domino)

Bon Dieu connait/Josephine c'est pas ma femme. O Nonc Helaire/ Josephine c'est pas ma femme.

The Good Lord knows, Josephine's not my wife. Oh Uncle Helaire/ Josephine's not my wife.

Hello Josephine Keith Frank

Hello Josephine/ well how do you do/ do you remember me my baby?? Like I remember you/ You used to drive your car/ through the drive-in window.

Saturday, March 8, 2025

Thursday, February 20, 2025

Monday, February 17, 2025

Wednesday, February 12, 2025

La Prairie a une Mémoire

The Prairie Has a Memory

Ashlee Wilson, 2024

La prairie a une mémoire. The prairie has a memory.

The prairie has a collective memory. Places retain une souvenance of what was before. There is memory in story of the plants that remain, the seeds in the ground, and if we are present enough it is revealed. In our stewardship of this environment we are invited to remember. The indigenous tribes of Louisiana were masters at management practices such as prairie burning and worked with the seasons and cycles of the year to maximize productivity with minimal impact. In colonial times settlers traveled by ship across oceans and made linguistic parallels between the prairie landscape and the open sea. Despite the decline of this habitat, the prairie retains its memory and so do we.

The feminine imagery displayed across the Cajun Prairie in the form of Marian grottos is a visible symbol of our reverence for the feminine as well as the deeper indigenous matriarchy that permeates our cultural memory. Cultures over the world recognize water goddesses as protectoresses over long voyages. In South Louisiana perhaps the most visible of these is Our Lady of the Assumption, known in Acadian culture as the Maris Stella or Star of the Sea, but also in Yemayá, the Yoruba water goddess.

The prairie has an outer and inner life. On the visible outside the folklore is French, American, Cajun or Creole, but underneath the deep-rooted grasses there are native seeds, as well as sacred indigenous relics that remain. Research of the origin of the name Prairie des Femmes (Prairie of the Women) has led to the story of it being a place where indigenous women stayed when their men left. This research has also manifested on a personal level into a tangible reverence for the land and recognition of the fragility of the loss of not just the prairie soils, but also the stories and the languages that existed here.

My act of restoration for the prairie has been to inhabit the Prairie des Femmes and act as a scribe for her folklore as well as a steward by encouraging her native flora and fauna. One of the proofs of this work has been the appearance in my overworked sweet potato field of the native medicinal pseudognaphalium obtousifolium, fragrant rabbit tobacco, known locally as vinéraire (vulneraire). I found it by its fragrance in the back of my prairie in 2011, and in a similar way to the gathering of Prairie des Femmes origin stories, I have begun to share this medicine with locals who have memories and need of it.

Ashlee Wilson, a native of Ville Platte, Louisiana, is a teacher, artist, and self-taught Louisiana French speaker. She is widely recognized for her writing, photography, and visual journals documenting her journey in learning Louisiana French, as well as her work with native plants and folk herbalism. Ashlee created the Prairie des Femmes blog in 2012 to chronicle daily life on her historical prairie. She is also the author of The Plains of Mary (2014) and the Ô Malheureuse collection (2019, UL Press). She currently teaches French at the Academy of the Sacred Heart in Grand Coteau.

The Prairie Has a Memory pays homage to her home, La Prairie des Femmes, in St. Landry Parish. This historic prairie, documented in records from the mid- to late 18th century, lies near the boundaries of the Attakapas-Ishak and Opelousas territories, just east of the sacred hills of Grand Coteau. Once a sweet potato farm, the land has become a site of restoration under Ashlee’s care. For over 20 years, she and her family have cultivated native plants, reintroduced traditional land stewardship practices such as periodic burns, minimal mowing, and abstaining from chemical herbicides, all in an effort to restore the prairie’s natural balance and preserve its memory.

Saturday, December 14, 2024

Thursday, December 12, 2024

Wednesday, December 11, 2024

Tuesday, December 10, 2024

Monday, December 9, 2024

Saturday, December 7, 2024

Thursday, December 5, 2024

Sunday, December 1, 2024

Saturday, November 30, 2024

Tuesday, November 26, 2024

Comme la Femme dit

From the Egyptian Book of the Dead Chapter 94, Prairie des Femmes Journal 2-2016, Tomb of Nefertari #pdfjournalaew

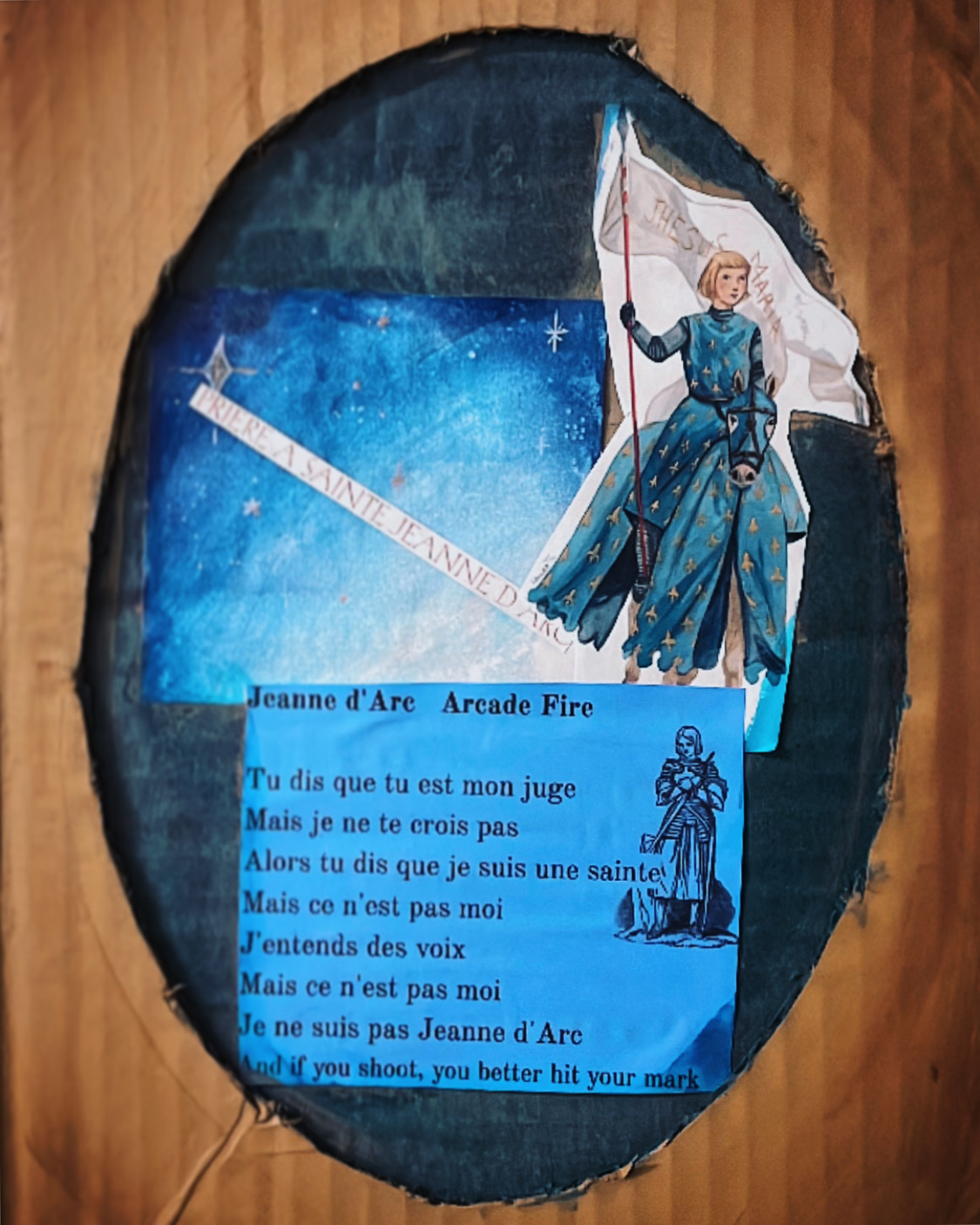

Joan of Arc week with the girls of the Sacred Heart

Joan of Arc week with the girls of the Sacred Heart